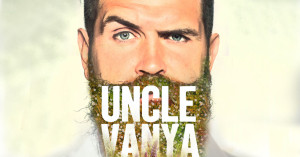

In 2010, the Guardian’s Susannah Clapp listed actor Jamie Ballard as one of her “ten best Hamlets”, alongside high profile figures such as Henry Irving, John Gielgud, David Tennant and Mark Rylance. Jamie played the Prince of Denmark in Jonathan Miller’s production at Bristol’s Tobacco Factory in 2008, but is now swapping tragedy for comedy as he’s about to take on the title role in Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya for Theatr Clwyd in Mold.

But hold on. People don’t generally associate the 19th century Russian playwright with laughs and giggles, do they?

“Chekhov thought of his plays as comedies,” says Jamie. “It was only his creative relationship with Constantin Stanislavski [the Russian theatre practitioner who staged a pioneering version of Chekhov’s The Seagull in 1898] that made the perception of his work all heavy and serious.”

Jamie is keen to extol the true virtues of Chekhov’s work: “If you come and see this production you’ll really see how mercurial his writing is, how unpretentious. It’s just people talking to each other in a very real and vital way. It’s not the ‘heavy theatre’ some people think it is. It’s people dealing with their problems and trying to do the right thing, to make the best of everything and get through life in the best way possible. Just like all of us really.”

Directed by Theatr Clwyd’s Artistic Director Tamara Harvey, this Uncle Vanya (a co-production with Sheffield Theatres) boasts a fresh adaptation by stalwart Peter Gill. What has Gill brought which is new to the play?

“We wanted to keep it period, as that is an important part of the play, but this adaptation is very of our moment and our voice. Very often, adaptations of Chekhov, particularly from the early 1970s, feel clunky. They’re not words I would use and they don’t fit well in my mouth. Peter’s version is very clever and incredibly dextrous, it crackles with life. Some past adaptations have simply been literal translations, but we don’t speak like that any more. This version fizzes with life.”

Uncle Vanya is about relationships (as almost all plays are), but it’s also about the unsaid, the undone, and the unrequited. It examines the separation between what a person thinks and feels, and what they admit to thinking and feeling. This dynamic is what Jamie finds fascinating and rewarding about the play.

“Every character has something they want to say, but doesn’t. We look at what they do say instead of what they want to say. There’s this fascinating tension and conflict with all the characters. It can be heart-breaking to watch, as you know what they’d like to say, but can’t.”

Jamie adds that there’s more to Chekhov’s plays than simply people talking to one another: “What a lot of people don’t think of with Chekhov is that the characters talk to the audience, they have soliloquies. The audience has that chance to get inside their true feelings, so in the next scene you know what they’re really thinking and feeling, but see them suppressing it.

“Every character is so three-dimensional,” he enthuses. “Tamara’s rehearsal room is incredibly free, she doesn’t like us to feel we have to fix something and carve it into stone. We’re constantly building up a tool-belt of emotions and choices and intentions that we are able to draw upon at any moment. No performance of this play will ever be the same, more so than any other I’ve done, because we’re constantly exploring it. It’s so well written but there’s plenty of scope to turn on a dime.”

In the play, a retired university professor who has lived for years in the city decides to move to his country estate, which is being run by his late first wife’s brother, the titular Vanya. But the professor’s arrival on the estate, along with his second wife, causes ripples among those who already live there, including Vanya and his niece Sonya. Themes of grief, jealousy and desire run through the play.

“Vanya starts to vocalise what he’s been suppressing. He’s been lying to himself for over 25 years, these feelings of suppressed emotion and grief over his sister’s death. It’s how that impacts on the people around him and what he projects onto them. Vanya is very complex, a very intelligent, educated man. He’s deeply caring and adored his sister and misses her terribly.”

How does Jamie connect with these deep-seated emotions in Vanya’s make-up?

“I have a nephew and a niece who I adore, and I have a brother who I worship. I also lost my mother eleven years ago, so there are things that have happened in my life that resonate with what’s happened to Vanya.”

Vanya’s complexity is more testament to Chekhov’s skill as a playwright.

“People say that Shakespeare was the master of writing about the human condition, but Chekhov is a close second. He is so good at writing fully-rounded characters, with all of their victories and failings and idiosyncrasies. Nobody’s ever just good or bad or a hero, they have all those elements.

“He’s writing about a very universal subject matter, about human interaction, what prevents people from finding happiness and what self-deception people employ just to get through the day.”

Uncle Vanya will be performed in the round at Theatr Clwyd, a performance style Jamie loves.

“It’s incredibly exciting, I love being in the round. I did it in a few seasons at the Tobacco Factory in Bristol, which is an intimate space, and I love the layout and being close to the audience. There’s nowhere to hide! There’s a minimal set, there can’t be big flats to block sight-lines, there’s just a couple of items of furniture. You can literally turn to your right and talk to a member of the audience, you can look in their eyes and they can have some live interaction with you. It’s so alive!”

Uncle Vanya can be seen at Theatr Clwyd, Mold, between September 21st and October 14th, 2017, before it transfers to Sheffield’s Studio Theatre between October 18th and November 4th, 2017. Contact Theatr Clwyd and Sheffield Theatres for more.

Theatr Clwyd, September 21 to October 14

https://www.theatrclwyd.com/en/whats-on/uncle-vanya/